How Bill Shankly changed the fans

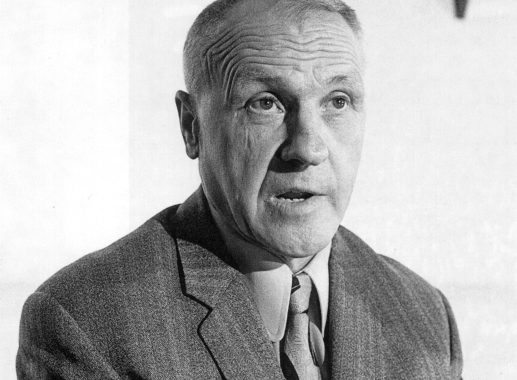

To mark the 100th anniversary of the birth of the great Bill Shankly, we've taken a look at the different areas of the club he revolutionised during his 15 years at the helm – and today we focus on the relationship between the manager and the fans.

If Bill Shankly epitomises all that is great about Liverpool Football Club, then Ian Callaghan can't be far behind.

It's 10.45am on Sunday, September 1, and the back-streets that cluster around Anfield are teeming with red.

Shuffling through the middle of a stream of bodies is Cally, hands wedged firmly in the pockets of his trench-coat, collar pulled up high to shield his chin from the breeze.

Head down, his only focus is on keeping his feet in sync with the thousands of others that are slowly pacing towards the entrances to the main stand ahead.

Out of nowhere, someone recognises his trademark smile, zig-zags past the oncoming traffic and says: "Cally, sorry to bother you, mate. You couldn't give us your signature there, could you? Thanks Ian, you were me old man's favourite of them all."

It's no problem at all - it never is. Cally could stop to sign a thousand more signatures before getting into the ground, where he'll watch his beloved Liverpool beat Manchester United 1-0 a day before what would have been Shankly's 100th birthday.

Each person would be greeted the same; with a beaming smile and a warm shake of the hand. There's no two ways about that. That sort of modesty and humility is unequivocal. It can't be turned on and off with a switch, because it's genuine.

Its why, even after chalking up a phenomenal 857 appearances in a red shirt, Cally is quite often the quietest person in the room, and when he does talk in his gentle Scouse tones, his friendly way and modest words are humbling.

It's why we almost walked straight past him at Anfield's Boot Room cafe earlier this week; because he was sat in the corner, sipping a cup of coffee, minding his own business as he very often does.

We were there to interview him about Shankly, the man who signed Cally as an apprentice and who took him under his wing for 14 years.

And when the interview is in full swing, Cally doesn't have to think on his feet for a new anecdote or quirk, he just tells it like it is, as though he's telling a friend in the pub what made the Scot so special: "He loved people.

"He'd spend a lot of time with the people, talking to them and signing autographs. He was a people's guy.

"He fell in love with the Liverpool people and they instantly fell in love with him because he made promises and he kept them."

Shankly knew of the Liverpool people before he took up the job as manager in December 1959. Prior to the Second World War, the Scot travelled there for a nose operation - and he made a handful of trips to Anfield itself to watch boxing matches.

He cheered as Peter Kane fought Jimmy Warnock and Ernie Roderick boxed the great Henry Armstrong, but there was no sign of Billy Liddell or Ronnie Moran.

His early experiences of Liverpool taught Shankly that the place was like the great, bustling Scottish cities and the people were like Scottish people. And this to Shankly was a good thing.

But on the terraces of Anfield, which had stood in place since 1892, when Everton played in front of what would go on to be christened the Spion Kop, there was something amiss, something not quite right.

"At that time, for a city the size of Liverpool and considering the potential support, the situation was appalling," Shankly wrote in his autobiography My Story. "The dyed-in-the-wool supporters were just hoping a miracle would happen and they would have something to cheer about.

"People on the Kop were shouting and bawling, but not with the same unity or humour or arrogance that made them famous later.

"Everton were in the First Division, of course, and I went to Anfield to see a Liverpool Senior Cup game. Bobby Collins turned Liverpool inside out, Everton dusted them up, and the atmosphere was awful. The mockery was embarrassing. It was pathetic. But, deep down there was something."

Phil Taylor had been Liverpool's manager prior to Shankly. He was a gentleman, who had earned the respect of his players. But, as Liverpool historian Stephen Done explains, he was probably too much of a gentleman.

"Taylor was a decent man, he was an honest man and he was hard-working, but because he was so typically a gentlemen, if the board told him how it would be done, he probably would have said, 'Yes sir, absolutely'.

"So he couldn't really change an awful lot. He didn't have that kind of personality where he was going to put people's backs up, he wasn't going to tread on people's toes.

"It doesn't mean to say that he didn't have the desire to win - I think he did, but he just didn't have that aggression. The fans weren't against him and they could recognise he was a decent guy, because at the end of the day, the fans didn't have an awful lot to cheer.

"Shankly arrives and he can spot quite early on that there is this amazing, potentially highly-vocal and animated bunch of people, who all pile into Anfield every other week without fail to support the side.

"The numbers didn't drop during the wilderness years. The people still came. They were loyal, but they needed something to give them a lift. And I think it says everything that he understood that once you have the fans on side, everything else will follow.

"Shankly knew that if the fans loved him and the team, they would support them throughout. But while anyone can do the standing on the side of the pitch and blow the kisses to the crowd while holding the badge, Shankly was genuine."

In the years that followed Shankly's retirement in 1974, that genuineness soon became apparent as letters penned by the great man to fans slowly began to surface.

"These were letters that would never go on the internet, that weren't going to be read by anybody else, but were just going to sit in someone's wallet for the whole of their lives and be treasured - that's genuine," said Stephen. "And his letters are astounding.

"The whole time he talks about 'You' the person he's writing to, and he's saying: 'You are so important,' and 'what you say means so much to me'. Shanks would write: 'I'm humbled by what you said'. And you know he means it."

This is the honesty Cally touched on in our interview with him and this is the decency that meant so many Kopites took Shankly into their hearts.

He was a staunch socialist, but he wasn't party-political or driven by dogma. His socialism was instinctive and was reflected in the bond he forged with the fans.

Socialism seeped into his soul due to the upbringing he had in Glenbuck and it defined how he treated everyone, especially the Liverpool fans who paid their every penny to watch his side play at weekends.

For Shankly, the supporters weren't the most important people, they were the only people.

"Nowadays, terms like 'socialist' and such might sound a little bit tired for the younger generations," said Done. "But in Shankly's day, it was really clear that when you identified yourself as a socialist, you cared about people and you cared about society.

"He made a famous quote in which he explained about the importance of everyone working together and helping each other.

"He believed that about the supporters, about the team and about the whole club in general. You all have to help each other and work together. You all stick together, something good will come out the other side."