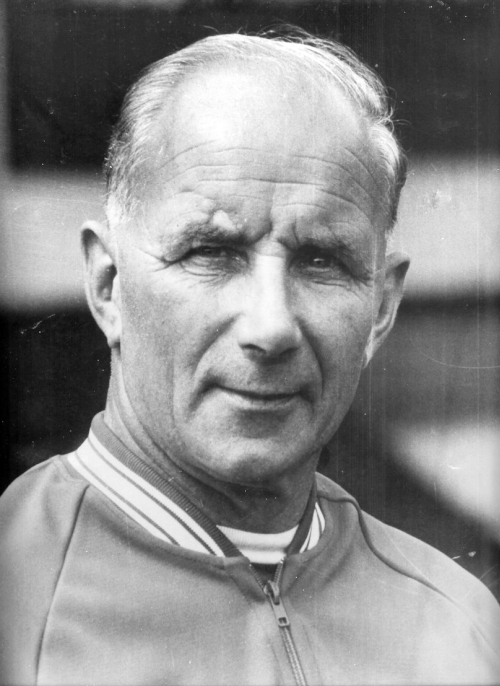

Long read: The mysterious Mr Bennett

Reuben Bennett's story is one of hard work and humility - but his contributions to Liverpool's most successful era should never be underestimated, nor forgotten, explains Scott Fleming.

- The full version of this article first appeared in Issue 10 of Nutmeg, a Scottish football periodical available by subscription at: www.nutmegmagazine.co.uk

Reuben Mitchell Bennett, a proud Aberdonian, a goalkeeper of some repute and an outstanding coach, lived an extraordinarily full life and played a significant role in Liverpool’s success during those glory years, and he fully merits his place in the catalogue of coaching icons produced by Scotland in the post-war era.

Born in December 1913, Reuben served an apprenticeship as a butcher before beginning his football career with junior side Aberdeen East End. He went on to appear for Hull City, Queen of the South and Dundee, but his playing career was interrupted by serious injuries to both his knee and his shoulder and the small matter of World War II.

Reuben’s war experiences would help mould him into the authoritative training ground presence he later became, according to his son, Michael Bennett.

“He was working down in London and playing for a works team when the war broke out,” Michael explains. “He went straight to the London Scottish to enlist but they were full up, so he was told to go home and wait for his papers to arrive, which they duly did. He was a Staff Sergeant Instructor with the Gordon Highlanders throughout the war, and volunteered for overseas duty on several occasions but was declined.

“He felt it was a wonderful training, because you were dealing with the full spectrum. He had actors like Stewart Granger and David Niven passing through his hands on basic training, but also the hard nuts from Glasgow. All the greats of management in that era served in the forces. They all knew that they had to find ways of working as a team and getting on, because the guy next to you could save your life. That kind of training is difficult to replicate.”

Reuben’s coaching career began in earnest in the 1950s, when he worked with Dundee, Motherwell and Third Lanark respectively, and it’s perhaps no coincidence that he alighted at Dens Park, Fir Park and Cathkin Park during particularly successful eras for those clubs. He was at Dundee when they won back-to-back League Cups in 1952 and 1953, he worked alongside former ‘Dee teammate Bobby Ancell when the famous ‘Ancell Babes’ Motherwell team was in its pomp, and was manager in all but name when Thirds won promotion back to the top flight in 1957.

Michael fondly recalls him and his childhood friend using the mythical old, steep-sided Cathkin Park as their own personal playground.

His father would also form important and lasting bonds during those years, with Ian St John – then a youngster at Motherwell – and Bob Shankly, brother of Bill, who would eventually take over as manager at Third Lanark. The only fully-fledged managerial experience Reuben himself had was at Ayr United between 1953 and 1955, but it did not go to plan and he eventually resigned.

“It was a problematic job,” Michael recalls. “He’d be coming home at midnight with all the admin, he didn’t have the support staff that modern clubs have, company secretaries etc. It really was not for him, and the final blow came when the directors signed a reserve centre-half from Celtic, when Dad had somebody lined up who later became a Scotland international. He’d had enough, there was too much interference from the directors.”

By the late 1950s Reuben’s reputation in the game was such that he was headhunted by then Liverpool chairman TV Williams in November 1958 to work as chief coach under Shankly’s predecessor Phil Taylor. Shankly arrived from Huddersfield Town just over a year later, and from there things moved very swiftly.

In one of the fastest and most impressive ascents to the top of English football ever seen (Brian Clough’s work at Derby County and Nottingham Forest is worthy of comparison), Shankly’s Red Machine won promotion from the Second Division in 1962, had lifted the First Division trophy by 1964 and in 1965 won the FA Cup for the very first time since the club’s foundation in 1892.

The likes of Paisley and Fagan were certainly playing a part, but it was Reuben who was closest to Shankly during those early years. The pair hailed from completely opposite ends of Scotland and were contrasting characters to an extent, but when it came to football the miner from Ayrshire and the butcher’s apprentice from Aberdeenshire were identical in terms of their obsession and willingness to pour every ounce of energy they had into the search for success.

Says Michael: “My dad spent an inordinate amount of time with The Boss in the early years. It was a close relationship, the day would start for them up at Harold’s the barbers, for a cup of tea and a read of the paper. Then they’d jump in The Boss’ car and off they’d go. They spent a lot of time on the road together, watching matches, looking at this, looking at that. Every so often they’d jump in the car and drive over to Huddersfield, just for a kickabout! They lived football – it wasn’t a job, it was a way of life for them.”

50 Men Who Made LFC: Reuben Bennett

From The Sunday Post labelling him the ‘Iron Man Of Anfield’, to Shankly calling him ‘the hardest man in the world’, to St John describing how he’d have anyone up against the wall that sowed internal discord, you could be forgiven for picturing Reuben Bennett as a cross between Full Metal Jacket’s Sergeant Hartman and Mr Mackay from Porridge. But there was more to him than that.

“If I were to say he was a player’s best friend, that would seem a complete contradiction, wouldn’t it?” Michael reflects. “He was very strong and tough, but extremely fair, and his whole raison d’etre was always to make sure that a player achieved his best. Even when he was living and working in Dundee, he’d come home to Aberdeen to be a Boys’ Brigade lieutenant on certain nights of the week. He always had that great interest in boys achieving the best they could, but you can’t do that if you’re constantly the stern, grinding man that the name ‘Iron Man’ implies. People should have seen how soft he was with my baby sister – nothing like an iron man.”

It was during the late 1960s and 1970s that a young Peter Hooton made his first Anfield forays, perched on a barrier in the Kop because he was too short to see what was going on otherwise.

Peter grew up to become the lead singer of Liverpool band The Farm, but more recently has returned his focus to his first love: LFC. A committee member for the Spirit of Shankly fan union and producer of the documentary Shankly: Nature’s Fire, which aired on BBC Two, he has now authored The Boot Room Boys: The Unseen Story of Anfield’s Conquering Heroes. With some vivid period photography, the book chronicles the work of Liverpool’s backroom staff from the 1950s right through to the late 1990s, and as such Peter is better qualified than most to provide an insight into the mysterious Mr Bennett.

“The impression I got was that it was a big coup getting him in 1958, when TV Williams asked him to come to Liverpool,” Peter says. “Shankly wanted his team to be the fittest in the world, and I think he saw Reuben as the taskmaster who could achieve that. They were regarded as the fittest team in the league, and that must have been down to his methods, which came from his army training.”

Indeed, looking back, the impact of Reuben’s fitness work is clearly tangible. When the second league title of Shankly’s reign came along in 1966, only 14 players had featured during the course of the season. Like Michael, Peter considers the picture of Reuben as the no-nonsense sergeant major a little too one-dimensional.

Various former players have described the severe stick they received from their Aberdonian overseer, with striker David Fairclough, for example, recalling how he arrived at the club as a top Liverpool schoolboy only for Reuben to tell him that he didn’t know how to kick a ball properly. Yet those same players remember Reuben with a great deal of fondness and gratitude.

“I couldn’t find anyone that had a bad word to say about him, even in all the autobiographies,” Peter adds. “It’s unusual, because he could be the enforcer, and they said he was a hard taskmaster, but they liked him, which doesn’t fit in with the image of someone who’s screaming and shouting.”

Shankly was a committed socialist and not afraid to air his political views in public, and whether it was conscious or subconscious, Peter believes the principles of socialism were inherent in the way the Boot Room went about its business.

“There was collectivism there. It was Shankly’s philosophy and his values, values which he’d inherited from his family in Glenbuck, where everyone helped each other. Politically we don’t know how all the individuals in the Boot Room voted, but you can really tell from their principles and integrity that they were to help each other. Shankly was the figurehead but no-one was bigger than anyone else, he wanted opinions from all the members of staff and encouraged that. In a way, it was almost like a coaches’ trade union. And any time they won anything, Shankly credited it to his backroom staff.”

After an uncharacteristically lean period in the late 1960s, the early 1970s was a time of great change at Anfield, with St John, Yeats, Hunt and co making way for the likes of Heighway, Toshack and Keegan, protagonists in the second great Liverpool side of the era, which would sweep up league, UEFA Cup and FA Cup honours before Shankly’s shock resignation in the summer of 1974. The Boot Room was not sheltered from the winds of change, with Paisley promoted to assistant manager – presaging his eventual coronation in 1974 – and Bennett reassigned to a ‘special projects’ role, the main thrust of which was scouting the opposition.

During this time Reuben received offers to go and work as a manager again, but those offers were rebuffed. Now in his 70s and based in Buckinghamshire, Michael was 13 when he went to Liverpool with his father, and had already moved seven times due to the nomadic nature of Reuben’s career. The Bennett family had found stability on Merseyside and that was not something to be lightly cast aside.

“He didn’t really want that, he could see what was happening in Liverpool and he was part of that,” Michael says. “Education was really important to my dad and I think my mother would have had a fit if we moved again, but I don’t think he had any desire to. He had a tremendous regard for everything about Liverpool.”

Under the quiet, self-effacing Paisley the Reds became ever more ruthless in their pursuit of silverware, and in 1977 they got their hands on the one trophy Shankly had coveted more than any other: the European Cup.

When asked which of Liverpool’s many triumphs meant the most to his father, Michael’s mind immediately flits to that 3-1 win over Borussia Monchengladbach at the Stadio Olimpico in Rome. “That’s what sticks with me most,” he admits. “Tommy Smith got that headed goal to make it 2-1, and I’d never seen my dad so animated in my life, jumping up and down, fist pumping. He was not a guy that wanted to be up front, but he loved basking in the reflected glory.”

Watch: Highlights of the 1977 European Cup final

Two months after Reuben joined the club, Liverpool had been knocked out of the FA Cup by Worcester City of the Southern League. Reaching the absolute pinnacle of the game all those years later was the culmination of much hard work by himself and his colleagues over the best part of two decades, and it must have felt like the end of an epic quest. If anything, he did well to limit himself to a few mere fist pumps.

It would be another nine years before Reuben’s service at Anfield finally came to an end. Even after Fagan had been succeeded by Kenny Dalglish, the young player-manager had kept his compatriot – now into his 70s – around and given him duties. Says Michael: “One thing I’d like to say to Kenny is that he was very good to my dad. We used to say, ‘For heaven’s sake, will you retire? Is Kenny going to have your death on his hands?!’ But he’d say, ‘Kenny said I’ve got a job for as long as I want it.’ They allowed him to make a contribution, and that’s all he wanted to do in the later years.”

In December 1989, one week short of his 76th birthday, Reuben Bennett passed away. At his funeral, which was so well attended the Everton management team could only find space on the family pew, the coffin was draped in a Saltire provided by Billy Liddell, the Fifer who was Liverpool’s goalscorer extraordinaire in the post-war period.

Reuben dedicated more than half a century to the sport of football. He didn’t earn great riches from it, and any fame that he accrued has faded in the 30 years since his death, but to linger on either of those things would be to miss the point. Like Shankly, he was of a generation for whom simply being able to make a living from the game they loved was reward enough. His popularity with Liverpool’s players may have partially stemmed from the colourful tales he would tell of his army years, but away from the Melwood training ground he was modest by nature and averse to giving interviews.

If it seems unjust that he rarely warrants more than a passing mention in the innumerable books, films and TV programmes documenting Liverpool’s golden era, then perhaps it’s worth considering that that’s exactly how the man would have wanted it.

“He’s been the quiet man, and that’s his choice,” Michael concludes. “When I go to these commemorative dinners, I think there’s a genuine affection for my dad, a regard and a respect. I never heard my dad speak ill of anyone. He’d never come home and say, ‘That so-and-so…’ And if he didn’t do it there, he wouldn’t do it anywhere. Football fame is a transient thing, and I’m happy to keep Dad’s name alive with some reputation. I can ask no more than that.”