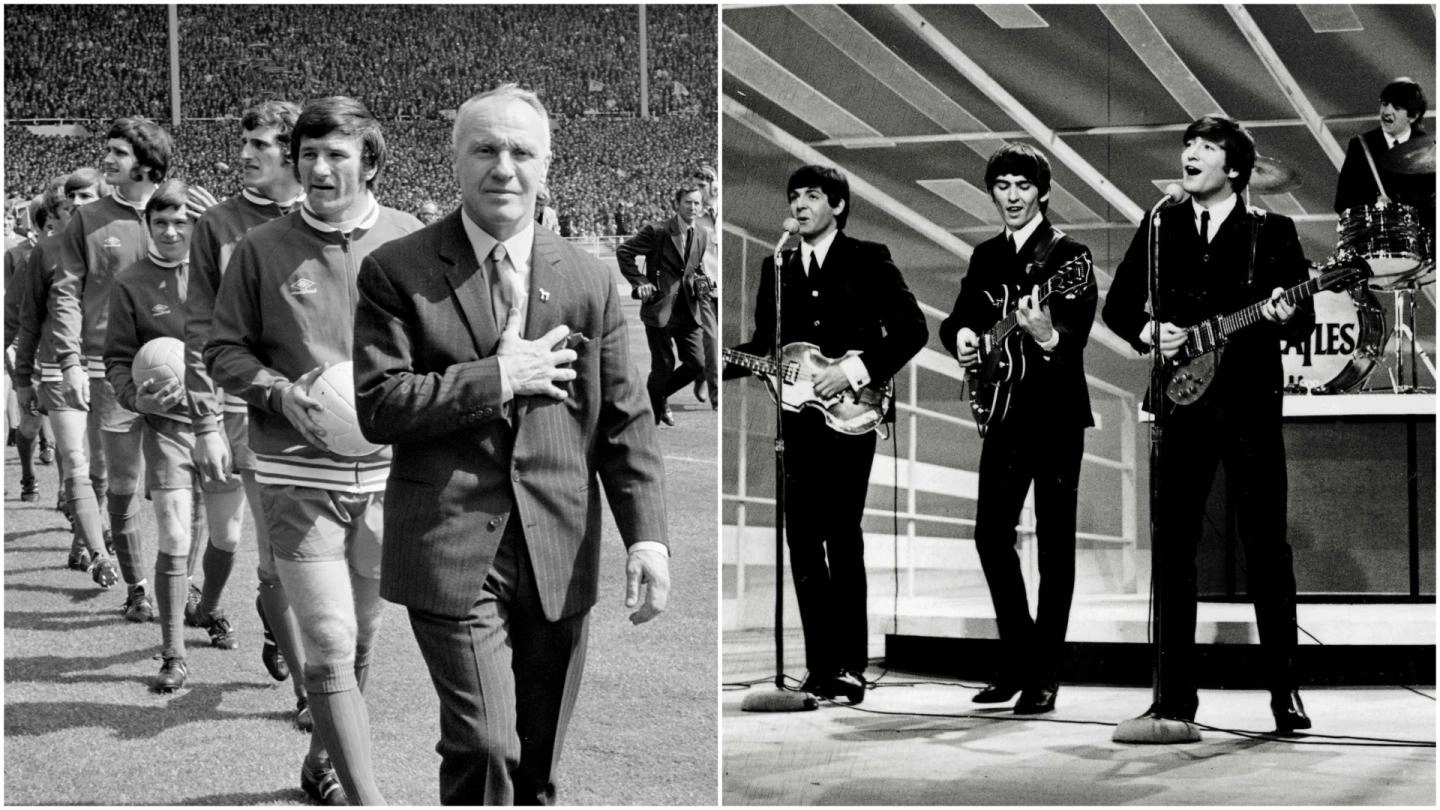

FeatureHow the Beatles and Bill Shankly's Reds made Liverpool the 'centre of the universe'

A special feature from the official matchday programme explores how the success of Bill Shankly's Liverpool side in the 1960s coincided with the explosion of Beatlemania all around the world...

Carl Jung called Liverpool 'the pool of life' in 1962. It was in a passage in a book, in a description of a dream, and though the Swiss psychoanalyst had never been to Liverpool and never would, if you interpret his words to mean 'the centre of the universe' – which was pretty much how visiting American beat-poet Allan Ginsberg described the city three years later – you'd have to admire his prescience.

Because in the middle of the 1960s, that's exactly what Liverpool was.

On Sunday evening, May 10, 1964, tens of millions of television viewers across the United States watched as Ed Sullivan announced that "tonight we have in our audience [on his eponymously-named show] one of the great soccer teams of England, the Liverpool team that won the English league title."

Cut to a middle row of seats in the audience at Studio 50, New York, and the big smile of Ron Yeats, then Ian St John, Willie Stevenson and Bobby Graham, flanked by stony faced trainers Bob Paisley and Reuben Bennett, all immaculate in dark suits and skinny ties. "Would you stand up, gentlemen?" exhorts Sullivan. "All of you, everybody up!

"Well come on now America, let's hear it for Liverpool!" The recently crowned champions, in the States for a five-week tour of 10 friendly games, were there to watch Gerry and the Pacemakers perform on the biggest TV show in the world.

Manager Bill Shankly was in Manhattan but not present at this 'telecast' on 1697 Broadway. How the Yanks would've loved him.

Three months earlier, four other Liverpudlians had performed five songs live on The Ed Sullivan Show to an estimated 73,700,000 viewers nationwide: All My Loving, Till There Was You, She Loves You, I Saw Her Standing There and I Want To Hold Your Hand.

During the second song, a ballad, the camera had panned to each sharp-dressed young 'mop-top' in turn: Ringo Starr on drums, George Harrison playing a dark walnut Gretsch guitar, Paul McCartney on his left-handed 'viola' bass. When it reached John Lennon and his black Rickenbacker, a caption appeared underneath: "Sorry girls, he's married."

The country's Saturday Evening Post documented Beatlemania thus: "It all began in Liverpool, a smog-aired, dockfront city that overlooks the Mersey River… Today Liverpool is the pop-music capital of the British Isles, and what newspapers have come to call 'the Mersey sound' dominates the English hit parade."

"Do you want to know what the Mersey sound is?" says one American critic. "It's 1956 American rock bouncing back at us." Only with a Scouse twist and shout.

Four months later, the Beatles bounced back home for the 'northern premiere' of their movie A Hard Day's Night, at the Liverpool Odeon (on the city's London Road) on Friday July 10, 1964.

There had been euphoric homecomings before, most recently when Everton brought back the FA Cup in 1963, but Castle Street had never seen anything like this. The group were driven from Speke Airport to the Town Hall in a police cavalcade with 200,000 fans lining the route – "people we'd known as children, girls we'd got the bus with," said Paul – and breaching the cordons time after time.

The funny thing about the surging Judys and straining bobbies in the photographs? They all seem so happy. The Beatles were welcomed by legendary local MP Bessie Braddock, an Evertonian and former pupil of Anfield Road School, and given the Freedom of the City before setting off to watch the film at the cinema.

It was mid-summer and the new football season was still a month away, the Reds preparing to defend a league title – their first for 17 years – that had been clinched at Anfield in front of the BBC's Panorama cameras and serenaded with She Loves You and Anyone Who Had A Heart.

The decade, which had begun to a backbeat pounding off the sweaty cellar walls of the Cavern on Mathew Street, now rode the roars of a rough-and-tumble Spion Kop.

"Liverpool was the place to be," wrote Reds player Tommy Smith in his latter-day autobiography Anfield Iron, "[and] the Fab Four were in tune with the times and also in tune with their home city.

"The football club's renaissance under Bill Shankly coincided with this explosion of popular culture on Merseyside. It was a hell of a coincidence, but it put the club in the vanguard of English football and even made our supporters famous. The fans on the Kop had taken to singing You'll Never Walk Alone, the stage song whose version by Gerry and the Pacemakers had topped the charts in October 1963."

Teammate Ian St John would recall everyone being "carried away by the Shankly indoctrination – we were the finest team and Liverpool was the finest city, in any way you could imagine. When success came so quickly, the wild talk was suddenly wild reality.

"Liverpool, which had seemed so immense and sprawling when [my wife] Betsy and I first arrived from Motherwell, had become our village – an excited, uproarious village. Other emerging stars could be seen around town – the Beatles, Gerry Marsden, Cilla Black – but the big clamour was for the autograph of a footballer."

On Sunday August 16, 1964, 24 hours after opening the new season at Anfield with a 2-2 draw with FA Cup winners West Ham United in the Charity Shield, the Reds embarked on an odyssey to Iceland via airports in Liverpool, London and Prestwick. In their first ever European Cup tie, they'd been drawn against part-timers KR Reykjavik.

Forward Roger Hunt wrote in his own 1969 autobiography: "[On the flight] we had a glorious view of Iceland, even in the dark, for one of the volcanic islands was throwing out fireworks, and the pilot took us over it three times before going in to land. We enjoyed the rest of our stay, too, for Reykjavik was a lovely place, the people were extremely friendly, and the air was even better than Blackpool's." Hunt scored twice in a 5-0 first-leg win.

The next day the Beatles were airborne, too, flying from London to San Francisco to begin a first US tour of 25 dates and total hysteria. "We had 17 years of being able to walk to the shops and now we can't even go out of the hotel on our own," said John. Hard lines, our kid.

The following weekend saw Liverpool beat Arsenal 3-2 – shown in the evening on the BBC's very first Match of the Day – and the Beatles play the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles.

Autumn came and went, and late November brought another first: the Reds playing in all-red, famously for the visit of Anderlecht in the first leg of the European Cup first round. They won 3-0, with Smith, 19 years old and quarried straight out of Anfield, wearing the No.10 shirt but playing a blinder in a flat back four.

In the three weeks before the second leg, when 'keeper Tommy Lawrence would keep the Belgians at bay brilliantly, the Beatles released the single I Feel Fine then the album Beatles For Sale.

The football, the music, the gear. If the Fabs would continue to conquer the world in the new year, the Reds had set their sights on Europe and, at home, a trophy that had eluded them for 73 years.

In the first round of the FA Cup, they won 2-1 at West Bromwich Albion, the goals scored by Hunt and St John and a penalty for the home team after Yeats had picked up the ball in the Liverpool box thinking he'd been fouled.

It took a replay, though, to see off lowly Stockport County in the next round, with Shankly skipping the first game at Anfield to go and watch Liverpool's forthcoming opponents in the European Cup, Cologne.

The first leg of that second-round tie on Wednesday February 10 finished goalless in Germany. The next day Ringo, then 24, married hairdresser Maureen Cox in London, 22 days after he'd proposed to her.

Back in the FA Cup, when the Reds travelled to Bolton Wanderers in the fifth round, 20,000 fanatical supporters went with them and saw Ian Callaghan head home the winner from a Peter Thompson cross.

A fortnight on, the Beatles were filming the movie Help! in the Bahamas, while a blizzard at Anfield forced the abandonment of the second leg with Cologne.

Three days later, the Reds were thwarted by England goalie Gordon Banks in a goalless FA Cup quarter-final at bogey team Leicester City.

The replay for that tie came within four days, on Wednesday March 10, and the gates at a heaving Anfield were closed 45 minutes before kick-off. Chris Lawler took the free-kick, Yeats cushioned the header, Hunt hit it so hard the ball cannoned off the inside stanchion and back out of the Leicester net. His 32nd goal of the campaign, Liverpool in the last four.

Another seven days, another monumental match, and goalless again in the rearranged second leg with Cologne. In the replay at Feyenoord's De Kuip stadium in neutral Rotterdam, it ended 2-2 and Shankly's side went through on the toss of a dual-coloured disc that came down red.

Over the weekend of March 27/28, all roads led to Birmingham. On the Saturday, the Reds beat Chelsea 2-0 in the FA Cup semi-final at Villa Park, with player-of-the-match Thompson carried shoulder-high off the pitch by jubilant fans; just around the corner on the Sunday, the Beatles appeared on the TV show Thank Your Lucky Stars, recorded at Alpha Studios in Aston.

Indifferent league form meant Liverpool would finish seventh this season, a shortcoming that would be splendidly addressed in 1965-66. Instead, destiny drew them towards Saturday May 1, 1965.

When the team headed for north London and Wembley Stadium for the FA Cup final with Leeds United, the Beatles were a few miles southwest at Twickenham Studios where they'd just filmed the scene in Help! where Ringo tries to remove a ring from his finger with slapstick results. One-nil (Hunt, 93 minutes). One-one (Bremner, 100). Two-one (St John, 111).

"It was a wet day, raining and splashing," recalled Shanks after the Reds made history in extra-time. "My shoes and trousers were covered in white from the chalk off the Wembley pitch as I walked to the end of the ground where our supporters were massed. I took off my coat and went to them because they had got the cup for the first time.

"Grown men were crying and it was the greatest feeling any human being could have to see what we had done. There have been many proud moments – wonderful, fantastic moments – but that was the greatest day."

Ee-Aye-Addio, we'd won the Cup, and on Sunday we brought it home. This time Castle Street had seen something like it, thanks to John, Paul, George and Ringo 10 months earlier.

Even so, the Echo reported, "skipper Ron Yeats and the team were greeted by roars of 'Liverpool! Liverpool! Liverpool!' from 50,000 throats in the vicinity of Lime Street, and St George's Plateau was a solid mass of people, with one senior police officer saying: 'This makes the Beatles' reception look like a vicarage tea party!'"

On the way to the Town Hall, according to St John, "Bill Shankly rode the [open-top] bus like an emperor." Strike partner Hunt had "expected a pretty wild welcome on our return to Liverpool but we were not prepared for what happened – I have never seen such a crowd."

Two days later, on a tide of Anfield emotion, the trophy was paraded in front of 54,000 fans by injured players Gerry Byrne and Gordon Milne, before Liverpool humbled mighty Internazionale 3-1 in the first leg of their European Cup semi-final with goals by Hunt, Callaghan and St John.

Of course, the Italian and reigning Intercontinental Cup champions would score three without reply in the return leg in Milan to reach the final, on their own ground, and beat Benfica.

The Fab Four were also in Milan at the end of June, performing the first of eight gigs in Italy at Velodromo Vigorelli, one-and-a-half miles east of Stadio Giuseppe Meazza, where the Reds had exited the European Cup so painfully.

By then, the Beatles had been awarded their own silverware in the shape of MBEs from Harold Wilson, the Prime Minister and Member of Parliament for Huyton.

"What will you do with your medals?" asked one reporter at the press conference. "Hang it on the wall," answered George. "Tuck it around my neck," said Ringo. "Keep it in a safe place," offered Paul. "I think I'll have mine made into a doorbell so that people have to press it when they come to the house," mused John.

"And what do you think now of Mr Wilson?" asked another hack. "We think of him what we've always thought of him," shrugged George. "He's a good lad."