How Bill Shankly changed training

To mark the 100th anniversary of the birth of the great Bill Shankly, we've taken a look at the different areas of the club he revolutionised during his 15 years at the helm – and today we focus on training.

The sun beats down on Liverpool's players as they are put through their paces at Melwood on a boiling summer's day in July 2013.

Studs rattle concrete in one corner of the complex as the dull thud of boots belting balls reverberates all around.

Brendan Rodgers stands in the middle of it all, surveying every touch, judging every move, while luminous green and orange bibs swarm around him in the blazing heat.

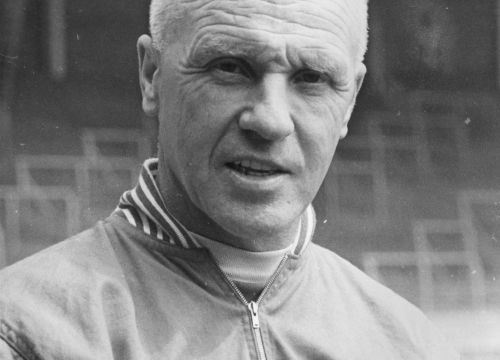

He studies his players with the same intensity Bill Shankly would watch Ian Callaghan strain every sinew, watch Roger Hunt gasp for breath in the 'sweatbox' or spot the Saint ease off a little.

"I would train in amongst them," Shankly wrote in his autobiography 'My Story'. "I would know who wanted to train and who didn't. Each player was being watched.

"Callaghan, for instance, had to be made to simmer down. He worked so hard on Saturdays that I had to say to him: 'Listen, son, you take it easy. Just you go through the motions'.

"Others had to be encouraged occasionally to do a little more. Once we were practising with the boards and I noticed St John was just going through the motions, so I said to him: 'This is to speed you up, not slow you down'."

Yesterday, we saw how Liverpool's players would train in the main stand car park outside Anfield before Shankly arrived.

They grafted on concrete and tarmac, grazed knees on gravel - and when it was time to build their strength, they ventured into the sanctuary of Anfield to work in a small gym inside the main stand.

Players like Ronnie Moran, Jimmy Melia and Alan A'Court would then slip into plimsolls and go running along the streets of L4.

Pounding their feet on the concrete, Tommy Lawrence and Roger Hunt, who were reserves when Shankly arrived, would run so hard on the unforgiving surface, in nothing but cotton pumps, they would finish up with ruined knees and ankles and hips.

For Lawrence, it was a battle to scale a flight of stairs or board the train back home afterwards because he had run so hard along the road.

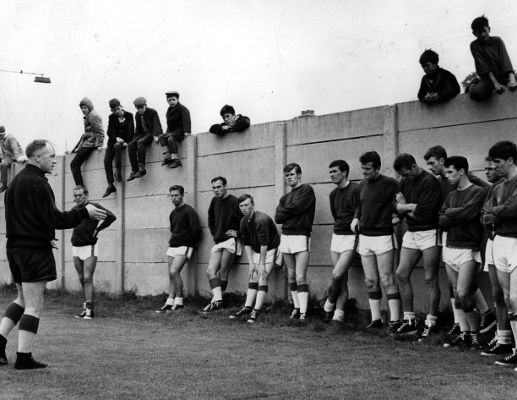

But from the day Shankly arrived at Liverpool, training at Melwood was planned scrupulously - and endless road-running was not on the agenda.

Every last act was considered and everything was mapped out on intricate, tabulated sheets, which would be circulated around his members of staff.

"Everything we do here is for a purpose," Shankly would warn his players. "It has been tried and tested and it is so simple that anybody can understand it. But if you think it is so simple that it is not worth doing, then you are wrong. The simple things are the ones that count."

Slowly but surely, Shankly made sure his methods and messages permeated the club and the squad.

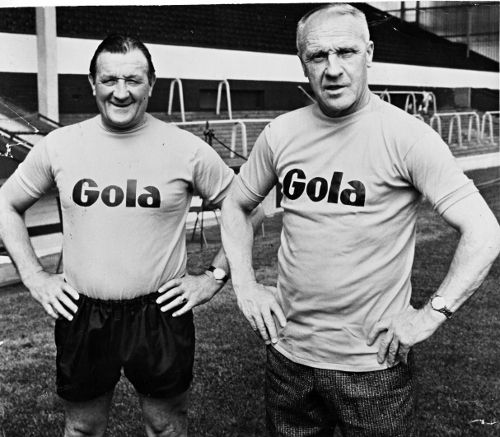

Before any training session, Reuben Bennett would lead the warm-up for roughly half an hour before the strenuous work began, because, as Shankly succinctly put it: "You wouldn't rev up your car to the hilt when you first started driving it in the morning or you might blow a gasket."

Once the players were warmed up, they were split into groups of six - lettered A to F.

Each team would be put through different functions simultaneously. So while A might focus on skipping or weight training, C would be working on jumping and E on abdominal exercises.

Circuit training would make Melwood a hive of flurried yet coordinated activity - and Shankly would oversee every routine, sounding his whistle to keep the players moving from one task to another.

Players were said to have been taken aback when he ordered them to train with the ball at their feet.

It's hard to imagine now, but something that is so fundamental to the training of players was a largely uncommon occurrence.

But Shankly drilled them on how to move the ball; how to drive it, chip it, control it and even head it.

"We brought out the training boards," said Shankly. "They would be set up about 15 yards apart and would keep the ball in play and keep the players on the move all the time.

"If the ball beat the goalkeeper, it would hit a board and be back in play again.

"We also had a 'sweat box', using boards like the walls of a house, with players playing the ball off the wall on to the next, a similar movement to the ones I used to see Tommy Finney practise at the back of the strand at Preston.

"The ball was played against the boards; you controlled it, turned around, and took it again."

Shankly's training sessions were constantly evolving, but they needed to be foolproof and he needed to know they would have the desired effect.

So one day, he decided to put his new method of training boards to the test and asked for Hunt, one of the fittest players within the ranks, to act as guinea pig.

Placing the boards 15 yards apart, Hunt was ordered to play the ball against one of the boards, take it, control it, turn, dribble up to the other board with just 10 touches of the ball. He'd then turn, repeat the exercise - and keep turning and repeating.

"We wanted to know how long this function should last," explained Shankly. "We were probing. After 45 seconds, Roger, who was as strong as a bull, turned ashen and I said: 'That will do, son.'

"Later Roger could do that exercise for two minutes."

This method of drilling players and stretching them to their capacity was applied elsewhere.

Rather than five-a-side games, three-a-side games would break out on pitches 45 yards long and 25 yards wide. The players would play five minutes each way and they would become so tired, play would have to halt.

But the exercises would continue with military precision and soon the boys could play in trios on wide pitches for half an hour and not be fatigued.

After all this was done, Shankly would round the day's events off with five-a-side matches. He'd join in with the players and battle against them like he was vying for a place in the team. Story has it he would even keep the game in full flow until his side won, such was his competitive streak.

"Enjoy yourselves, boys," the great man would say.