How Bill Shankly changed Melwood

To mark the 100th anniversary of the birth of the great Bill Shankly, we've taken a look at the different areas of the club he revolutionised during his 15 years at the helm – and today we start with Melwood.

Players enter through frosted glass doors embossed with a towering Liverbird when they arrive at Melwood nowadays.

Sweeping past the plush charcoal-grey couches and widescreen TVs, they make their way through the main reception area, with its stone-grey tiles, wooden-panelled walls and white-washed ceilings.

A stairway reaches up to the left, where on the other side of a fort knox-style electronic door is the canteen, the manager's office and rooms where scouts, performance analysts and coaches pour over footage of current and potential players.

Back in the reception, the European Cup stands proudly, enshrined in a gleaming glass box, with a quote from Rafael Benitez stencilled underneath. It reads: "To me, being part of Europe's elite is central to this club's ethos."

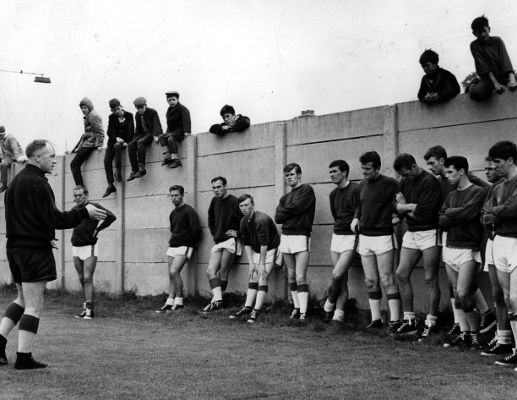

But when Bill Shankly arrived at a dilapidated Melwood training ground in late 1959, Liverpool hadn't the faintest concept of what it meant to play in Europe - never mind expect a place at its top table as some form of birthright.

"It was a sorry wilderness," wrote Shankly in his autobiography 'My Story'.

"One pitch looked as if a couple of bombs had been dropped on it. 'The Germans were over here, were they?' I asked.

"Tom Bush, the old Liverpool centre-half, took my wife Ness and me round to look at houses for the players and we called to see the training ground at Melwood.

"It was just a wilderness, but I said to Ness: 'Well, it's big and it can be developed. At least there is space here'."

It's hard to imagine it now - as you pace in past the neatly trimmed grass verges, with Porsches and BMWs scattered about on the pristine tarmac.

But Melwood, Liverpool's home since the early '50s, was overgrown and falling into disrepair. Its centre-piece, an old wooden pavilion, stood alongside a crumbling air-raid shelter.

Inside, the facilities were woeful; there was no heating and the paint was peeling away from walls. Outside, things were no better.

The pitches were smattered with bare patches, divets and dirt, and Shankly observed how there were: "Trees, hills, hollows and grass long enough for Jimmy Melia to hide in standing up."

Melwood was essentially a cricket pavilion - a school called Saint Francis Xavier had once stood in its place in the leafy suburbs of West Derby.

Father Melling and Father Woodlock, two priests at the school, had even given Melwood its name when they merged their own together.

Their land was sold to Liverpool Football Club during the inter-war period and had been allowed to fall into disrepair right up to the point Shankly first set his eyes on it in December 1959.

"But that in itself didn't really matter, because the club didn't really use it much," explained Liverpool historian Stephen Done.

"Before Shankly, they made all the players come to the main stand car park at Anfield, and they did a lot of their work there.

"Imagine it now, the players working on concrete and tarmac. There was a small gym in the main stand and they did all of their weights and lifts and all that kind of stuff there."

Such inefficiency was not unique to Liverpool; it was true of most football clubs around the country at the time. A very typical way of doing things had pervaded for what seemed like an eternity.

But Shankly decided on the spot that things had to change - and he returned to Anfield on the very first day he toured Melwood to figure out how he was going to revolutionise the club's training ground.

With ruthless efficiency, things began to change almost instantly. The old pavilion was given a makeover and painted on the inside.

Ground-staff from Anfield were called to Melwood to work on the pitch until it was of a standard Shankly approved of.

Stephen Kelly, who wrote Shankly's biography in 1997, observed: "Tarting up Melwood might not have seemed crucial, but it was important to Shankly.

"It was important that his home was spick and spam, reflecting the cleanliness and decency of the family. It was all part of his working-class culture - loyalty, cleanliness, honesty."

Over time, the cricket pavilion was levelled and cultivated and rebuilt brick-by-brick until it resembled the building which stood at Melwood until 13 years ago, when it was redesigned by Gerard Houllier.

The new pavilion had suitable changing facilities installed for the Liverpool players. Shankly added in a gymnasium and a sauna, but he decided against having a place where players could eat.

"I felt it was most important that, after training, the boys should have a cooling-off period before having a bath and a meal," explained Shankly.

"The 45 minutes between the end of training and arriving back at Anfield was just right. If you have a hot bath when you're perspiring, you perspire all day.

"Our system prevented the players from catching colds and it also made sure that they were not strangers to their home ground."

Looking around Melwood today it's hard to conceive of the place as being overrun and decrepit - but then again, walk into any club's training facility today and it's a far cry from the place's humble beginnings.

All clubs have had to revolutionise their training facilities to move on, but by the time Bob Paisley took over from Shankly in 1974, he had the foundations in place to go on and conquer Europe.

[SLIDESHOW]